In Jordan and Egypt, quiet qualms that Palestinian elections will boost Hamas

On a rainy evening in mid-January, the heads of Jordanian and Egyptian intelligence arrived in Ramallah for a sudden, unannounced meeting with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas.

Though senior Palestinian officials later insisted that the get-together had been scheduled months in advance, the timing was suspicious. Just two days earlier, on Friday night, the aging PA president had issued a formal decree ordering the first Palestinian national elections in over 15 years.

According to reports in both Hebrew and Arabic media, the two intelligence chiefs left convinced that after years of wishy-washy election pledges, Abbas was serious this time: Palestinians might actually see a national vote.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

Free Sign Up

Both Jordan and Egypt have issued rote statements declaring their support for Palestinian elections, vowing to offer whatever necessary to help them come to pass. Both are fully aware that the Palestinian leadership has long lost popular legitimacy in the eyes of its public.

But both of the Palestinians’ key partners also have deep reservations about a vote that they believe could bring Hamas back into the Palestinian Authority political system, officials say. Both countries are at odds with Hamas, an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood that opposes the regimes in Cairo and Amman, although they have learned to work with the terror group when they must.

Viewed from Jordan and Egypt, a resurgent Hamas could not only complicate matters in intra-Palestinian politics but even pose a threat to their own security. It could also interfere with the mission of restoring frozen ties between Ramallah and the United States, which both Amman and Cairo have an interest in.

“Jordan and Egypt view Hamas as a terror organization, [but] they see [the election] as a national security issue that is bigger than simply Hamas,” said former PA official Ghaith al-Omari, a senior research fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas meets with the heads of Egyptian and Jordanian intelligence, aided by his own intelligence chief Majed Faraj on January 17, 2021 (WAFA/Thair Ghanayem)

Palestinian leaders have repeatedly promised to hold elections since the last vote was held in 2006, when Hamas swept the Palestinian parliament in a landslide victory over its Fatah rivals who were riven by factional squabbles and widely seen as corrupt.

The terror group’s victory led to a fragile unity government between Fatah and Hamas. Following an international boycott, the unity government collapsed; the two rival Palestinian movements then conducted a bloody struggle for supremacy in Gaza.

Hamas again emerged triumphant, leading to the long-running rift in Palestinian politics: Hamas rules in Gaza, while Abbas’s Fatah movement controls the West Bank. Fear and mistrust between the two main factions — combined with a desire to avoid losing power — have torpedoed every feint toward elections over the past 15 years.

A diplomat from an Arab country told The Times of Israel that Amman and Cairo are still not convinced that the elections will actually take place. But if they do, there’s little reason to think that Hamas would not perform well again, the diplomat said.

“The Jordanians and [Egyptians] don’t think they’re going to happen in the end, but if they do it’s the same set-up as 2005-2006, so it’s clear that the result is going to be the same. This is what we’re concerned about,” the diplomat told The Times of Israel.

Palestinian supporters of the Fatah movement demonstrate in the West Bank city of Hebron, June 5, 2020. (Hazem Bader/AFP)

Much as in 2006, Abbas’s Fatah movement is deeply divided, and the long-serving president faces rivals at every turn: jailed Palestinian terror convict Marwan Barghouti, Emirates-backed Mohammad Dahlan, and former PA chairman Yasser Arafat’s nephew Nasser al-Qidwa, who has emerged as a harsh critic of Abbas.

In recent weeks senior officials in Fatah have taken shots at one another on social media. A highly publicized visit by senior PA official Hussein al-Sheikh to Barghouti — reportedly in an attempt to convince him not to run — did not seem to succeed.

In 2006, half of the legislative seats were contested on a district-by-district basis. Fatah saw multiple candidates run against each other in many districts, splitting the vote and handing a victory to Hamas.

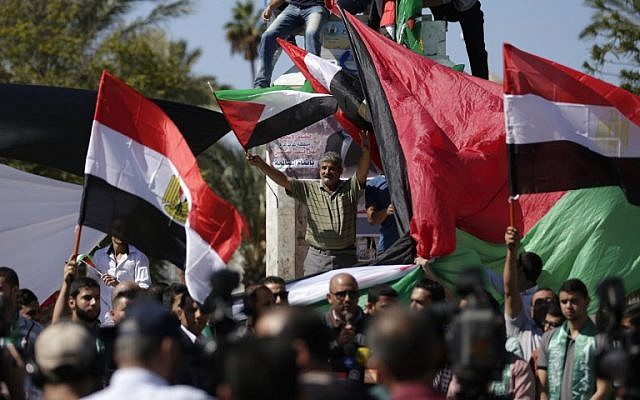

Palestinian supporters of Hamas attend a rally marking the 25th anniversary of the Islamist movement’s foundation in the West Bank town of Ramallah, December 14, 2012 (Issam Rimawi/Flash90)

Fatah officials who spoke to The Times of Israel said that the Egyptians have “concerns” about a Hamas victory, given the rifts within Fatah.

“Egypt is certainly apprehensive. They’re concerned about Fatah’s unity,” said Fatah Central Committee member Azzam Al-Ahmad in a phone call in late February.

But senior Palestinian official Ahmad Majdalani argued that a new elections law — which chooses parliamentary representation solely according to a national popular vote — would prevent a Hamas landslide.

“The new elections law prevents any side from achieving a majority in the legislative elections. Every faction will need to make alliances — either within the framework of the elections or afterward,” Majdalani said.

We’re all brothers in arms

Egypt and Jordan’s hesitations stem in part from the multilayered power struggle sweeping the region. Hamas is decisively in the camp of Qatar and Turkey, who have frequently clashed with Egypt and Jordan’s allies — the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

But both Jordan and Egypt also have tangled histories with Hamas, which until recently was a formal part of the Muslim Brotherhood and is still broadly aligned with the Islamist group.

“Their worry is that Hamas will win in the elections, and that will complicate the regional situation,” said Majdalani, who participated in a series of recent negotiations between Palestinian factions.

Palestinians gather in Gaza City to celebrate after rival Palestinian factions Hamas and Fatah reached an agreement on ending a decade-long split following talks mediated by Egypt on October 12, 2017. (AFP Photo/Mahmud Hams)

Egypt’s current regime, led by Abdel Fattah el-Sissi, came to power in a military coup against a Brotherhood-led government. In the years since, Sissi’s government has relentlessly pursued the Brotherhood at home, seeing it as an existential threat.

At the same time, Egypt and Hamas have been forced to coordinate. Egypt controls the all-important Rafah crossing into Gaza, and regularly opens it or closes it to exert pressure on Hamas.

“Egypt is accommodated with the status quo. They don’t like Hamas, ideologically. But Egypt has also gotten everything it wanted on border security, tunnels, eradicating radical Islamists, and so on,” said an Egyptian political analyst, who described the Egypt-Hamas relationship as a “fait accompli.”

Fatah official Azzam Al-Ahmad, left, visits Moscow, Russia, Feb. 12, 2019. (AP Photo/Pavel Golovkin)

In Amman, the Hamas-aligned Jordanian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood has long constituted the most serious organized opposition to King Abdullah II. The monarchy has sought to demobilize the Islamists, including by formally banning the party last year.

A Palestinian official claimed that Jordan and Egypt objected to allowing Hamas to participate in Palestinian elections, fearing it could increase pressure on them to enfranchise the Muslim Brotherhood.

“The Egyptians and Jordanians are worried about the Muslim Brotherhood gaining legitimacy in the Palestinian system because this could lead the US to push their own governments to similarly allow the Muslim Brotherhood to participate in their election system,” the official told The Times of Israel.

Beyond a symbolic victory for the Muslim Brotherhood at home, handing Hamas a platform in the West Bank could also pose a security challenge on Jordan’s border, which abuts the West Bank, al-Omari said.

“For Jordanians, the main concern is having Hamas in the West Bank. That’s not what they want from a political or security point of view. To them, it’s a national security, border security issue,” al-Omari said.

Palestinian protesters carry a giant key during a protest in front of the Israeli Embassy in Amman, Jordan, Thursday, May 15, 2014. (AP/Mohammad Hannon)

Both countries are also concerned that a Hamas win will chill efforts by Ramallah to renew ties with Washington.

The PA cut formal ties with Washington in 2017 following former president Donald Trump’s announcement that the American embassy would move from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Jordan and Egypt see the Palestinian proposal as currently outlined — a vote followed by a unity government with Hamas — as disastrous for any attempt by the PA to restore its relationship with newly elected US President Joe Biden.

Officers from the Hamas national security force carry a model of the Dome of the Rock while marching during a parade against Israeli security initiatives in the Temple Mount, in front of the Palestinian Legislative Council in Gaza City, July 26, 2017. (AP Photo/Adel Hana)

For the US, providing aid to or having formal diplomatic relations with Hamas — which it classifies as a terror group — is likely out of the question.

“Having Hamas in the system would make that very complicated if not impossible, and their concern is that this will basically bring us back to a situation similar to 2006. Both the Jordanians and Egyptians see stabilizing US-Palestinian relations as an important step for stabilizing their immediate neighborhood,” said al-Omari.

A State Department spokesperson said “the US and other key partners in the international community have long been clear about the importance of participants in the democratic process accepting previous agreements, renouncing violence and terrorism and recognizing Israel’s right to exist.”

From Cairo, with love

Egypt has so far played the largest role in pushing the elections forward. A round of election talks was conducted under the watchful eye of the Egyptian intelligence services last month in Cairo. Egypt even opened the Rafah crossing with Gaza indefinitely for the first time in years as a show of goodwill.

Why would Cairo work so hard on elections that might not come to pass — and which may end up harming its interests? Egypt faces its own challenges in Washington: while the Trump administration waved away human rights violations, the Biden administration has pledged to crack down.

The Egyptian political analyst suggested that by facilitating Palestinian peace talks, Egypt gets to play the role of diplomat and show itself as an influential player in the region. And if the elections don’t happen anyway — so much the better.

“This is part of the Egyptian attempt to reboot relations with Washington… to show itself as an actor with its own cards, that’s engaging on the issues,” said the Egyptian political analyst.

Moreover, Egypt jealously guards its role as mediator in the endless Palestinian diplomatic shuffle. Most of the failed Palestinian reconciliation talks in recent years have been held under Egypt’s aegis — a reminder of when Cairo truly was the diplomatic heart of the Arab world.

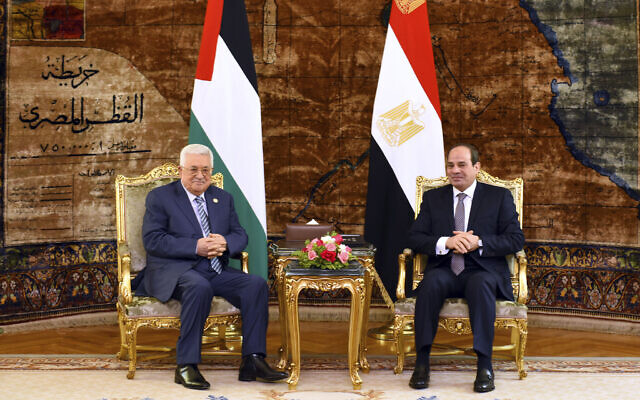

In this photo, Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, right, meets with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, April 21, 2019, in Cairo, Egypt. (Egyptian Presidency Media office via AP)

“Egypt satisfies all sides — Qatar can’t play that role, because they’re too pro-Hamas,” said the Egyptian political analyst. “The Emirates are too close to [Abbas rival] Mohammad Dahlan, and Abbas would never accept that. Saudi Arabia is disengaged. Egypt satisfies not only Fatah and Hamas, but Israel as well, because they trust the Egyptians.”

But while Cairo serves all the parties’ interests, it is not irreplaceable. In the past, the Palestinians have conducted talks in Istanbul and Doha, raising Egyptian hackles.

“The Egyptians fear that if they don’t play this role as convener or mediator, Turkey and Qatar will take over,” al-Omari said, naming two of Egypt’s regional rivals.

Abbas still has numerous exit ramps to ensure that the planned Palestinian elections never take place, as both Cairo and Amman seem to believe. But as the Palestinian election push gains momentum, both may need to start seriously planning for the day after.

“The Jordanians and Egyptians have a very tight rope to walk because nobody wants to be seen as against elections,” al-Omari said. “On the other hand, there are serious foreign policy and national security concerns that they have.”